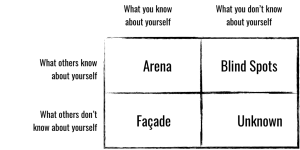

What is the Johari Window?

A model to increase one’s self-awareness, developed in 1955 by merging the names of it’s creators, Harry Luft and Joseph Luft.

It consists of a 2-by-2 matrix divided by “what is known” and “what is not known” as well as “by yourself” and “others”.

What does the model tell me?

The basic assumption is that we all have:

- An Arena

This is the stuff that I know about myself and others, too. Hence, the follow on assumption: The bigger your arena, the better you know and are open about yourself. The bigger your arena, the more authentic, trustworthy, potentially resilient and stable you are.

- Blind Spots

The stuff we don’t see, but others do! We can decrease our blind spots through feedback.

- A Façade

The stuff that we hide, in other words: What we know about ourselves, but others don’t. We can decrease our façade by sharing authentically what we are pretending, shying away from, scared of, ashamed of etc..

- An Unknown Part

The black box. What neither you now others know. That’s the box of lucky hits, meaning: If you engage in a process of accepting feedback and sharing yourself, chances are things might surface that neither you nor others knew about you.

How to increase my arena?

#1 Feedback

Now, most of us utterly dislike feedback! That is because in almost all work settings, “feedback” (especially the much hated ‘annual performance review’) serves as an opportunity for your boss to blow off some steam. A terrible session you have to sit through, listening to a “positive-negative-positive-sandwich” where someone else tells you off (and most of the times you cannot tell them off back as you are somewhat lower in the hierarchy).

This is NOT what we mean by feedback.

To us feedback (done well) is this:

- There is no negative or positive. Every behavior will be interpreted differently – depending what context it is in (for instance: being very angry might be massively inappropriate in one context but massively appropriate in another – in itself it is neither good nor bad).

You (as the feedback giver) …

- are disclosing yourself in a responsible manner. You SHARE your feelings towards the behavior of a certain person. You may give advice, but you understand that the person has a choice to take what (s)he wants to take. Hence, your advice (really) is just a recipe on how you would wanna be treated/ what you would have needed in a certain situation.

- understand that: Feedback maybe tells you something about the receiver, but definitely tells something about you (the feedback giver).

- Follow a structure like the one we invented:

- T – You name the triggering event/ situation/behavior

If you can remember one – sometimes we actually can’t we just have a vague feeling and that is (in the way we like to give feedback) ALSO ok!

- E – You name how that situation makes you feel or maybe “triggers” you

And let’s be concise with this. It can be one of the 4: Fear, anger, sadness or joy. “I feel that you should have done xy” or “I feel you are an idiot” does not express feelings. That expresses what you think. If you struggle just pick one of the 4 feelings named above.

- S – You share the story that your brain is telling yourself around why this particular feeling (and not any other feeling) emerges

For instance: “I really wanna get the client and in my world, our voices should be slower and more calm, if we want to induce trust on the client’s side.” (see example from the video)

- C – Optional: You share the consequences of what happens if everything just stays as it is

For instance: “If I keep feeling anxious when I let you pitch, I don’t wanna give you a good evaluation”

You (as the receiver)…

- understand that if you start defending yourself, telling your feedback giver that her/his perception is false or judging their feedback in any way, the only reaction you will likely harvest is that NEXT time they will be less open with you. They will likely fear your judgement (even if they don’t tell you that).

- understand that your most powerful reaction is to listen, and to maybe ask for clarification in a non-defensive way.

- say thank you in the end. Not because it is expected. But to honour that the feedback giver has been brave, too. (S)he has put herself/himself in a position where (s)he might potentially hurt you or make you angry. And if the feedback giver was honest, (s)he has rather shared something about her/himself than about you.

- May respond with the same T-E-S-C structure if you like: “Your feedback (T) made me feel xxx (E). What this means to me is xxx (S). And the result of that is xxx (C).”

#2 Sharing

Sharing for most people is actually harder than giving or receiving feedback. Simply because you yourself have to dig up the energy within you to share things you potentially do not want to put on the table.

We do not have any concrete rules for sharing, but from experience we know that thinking about “What do you wanna let go?” is a great question to start with.

Powerful questions for feedback and sharing

What do you pretend?

What side of you have you been hiding and are still hiding?

What pain are you just not getting over?

What emotion do you struggle with the most: Fear, anger, sadness or joy? What is great about your life because it’s like that? What is bad about your life because it’s like that (What are you missing out on?)?

How is your most painful memory shaping your life today? Which areas of your life does it affect and how?

What needs to heal?